As you know, there are many roles in an anime production, all of which for the most part act as essential cogs in an entirely way too convoluted machine with the end goal of churning out a finished product. At the very top we find the Series Director (監督, kantoku) head of all operations directly related to the anime. Below them sit the Episode Director’s (演出 enshutsu) as well as any assistants.

Episode Directors, by definition, are the ones tasked with overseeing the staff related to their particular episode. From animation, to color selection, to photography, and even monitoring the voice acting, they are present on every step of the ladder should they choose to be. Some may delegate those responsibilities to others they deem better equipped to handle them, though the truth remains that regardless, they’ll always be outranked and able to be overridden by the Series Director at anytime. More often that not, on healthier productions the Episode Director will also storyboard their own episodes, adding another layer of intimacy surrounding their involvement.

With this post we hope to dive into the many different production backgrounds, as well as how those roles may aid (or detract) from the esteemed position at the top!

Animation (作画 sakuga)

The most common of creative backgrounds also intuitively happens to be the best represented position among the industry. Animators comprise the bulk of the staff within a studio and after enough training or experience animating, some may wish to take the next step and try their hand at directing. Many of the best directors come from animation backgrounds and the reasoning is fairly obvious. In the same way that skilled animators are tasked with the composition and layout of their cuts, a director holds the same responsibility only they’re now overseeing the entire episode!

The clear quality which they possess is a creative vision from the get-go, an understanding of action, spacial awareness, flow, etc. all stemming from their animation roots. They’re able to give intricate and clear instructions to the animators working under them (shoes which they themselves once filled) to carry out their vision. In addition to having the means to step in and contribute hands-on corrections or animation of their own if needed.

In addition, an animation background will likely result in a very large list of contacts, since this is an industry comprised mostly of freelancers, animators are constantly shuffled around, picking up acquaintances as they go. So, when a particularly strong and/or idiosyncratic animator gets a series of their own, impressive animation spectacles are often the result. Shingo Natsume’s One-Punch Man and Mitsuo Iso’s Dennou Coil being prime examples of these animator influences carrying over as directors.

There are too many examples of animator-turned-director to list them all, the most famous director of all time Hayao Miyazaki is also one of the best animators who ever lived. Hideaki Anno, Hiroshi Hamasaki, Naoko Yamada, famous action directors Tensai Okamura and Masahiro Ando, as well as some celebrated minds, often categorized for their influential works such as Mamoru Hosoda, Masaaki Yuasa and Yoshiaki Kawajiri just to name a few.

In more recent years we’ve seen the digital age we live in spawn directors with connections all over the globe. Tatsuya Yoshihara‘s efforts on Black Clover are well documented. Chengxi Huang, Hakuyu Go, Kenichi Fujisawa and even Itsuki Tsuchigami, have made their marks on the industry via spectacularly produced episodes that double as must-watch events for the sheer amount of talent amassed in a single place at one time. It’s particularly interesting to note web-gen animators-turned director such as the previously mentioned Yoshihara, express certain liberal freedoms in their work. An air of easiness and willingness to approach problems under a different lens, something that a more traditional background may not teach.

Producer (制作 seisaku)

Another of the more “natural” positions through which one would reach the director seat is via being already involved in production side of things, usually from the Production Manager (制作管理 seisaku kanri) and Production Assistant (制作進行 seisaku shinkou) positions, there is a very clear trait which they excel at: organization.

Having already been involved with administration practices, an individual with a producer background will likely have an easier time deciding how to distribute resources, as well as time management skills to make the project run as efficient as possible (easier said than done with the current state of the industry), in addition to having already formed contacts with staff to call upon, since that was already a large part of their former job title.

While the skill-sets between the two aforementioned positions have a fair bit of overlap, where they do not is in the creative process. Some producers-turned-director may be very inspired to create original works of their own accord, while others, such as Noriyuki Abe (YYH, GTO, BLEACH) for example, would prefer to take up a management role and oversee the production of other people’s stories and ideas, ensuring their staff are in the best possible position to succeed. Nothing wrong with either situation of course, loads of successful anecdotes can be found among both!

In some cases these directors will decide to not storyboard their own episodes because of their incapacity to draw (the late Isao Takahata being the best example, as he always used to rely on the likes of Hayao Miyazaki, Yoshifumi Kondo and Osamu Tanabe to produce his boards, while he dictated his vision). A lot of directors that came through a production background are often found in studios like Bones and Trigger to reliably process boards by more talented animator-to-director storyboarders, people like Ikuro Sato being a prime example of this.

Famous directors to come from this background are the already mentioned late Isao Takahata, Shingeki no Kyojin’s Tetsuro Araki and his pal God Eater’s Takayuki Hirao, as well as Cowboy Bebop’s Shinichiro Watanabe. Also, even if they didn’t necessarily start as animators, you can’t deny that people like Kunihiko Ikuhara and Shigeyasu Yamauchi definitely made their mark on the industry.

It’s worth noting however, although we have mentioned that some directors may not be very good at drawing, there are exceptions, people that have learned through practice after they became directors and are -apparently- very capable animators, such as the aforementioned Tetsuro Araki (credited various times as Key Animator by the pen-name of Saburo Mochizuki).

Photography (撮影 satsuei)

And we finally get to the more uncommon and also fairly recently formed paths to become a director. The transition from the photography department to director is not all that logical, as they are not directly involved on the animation nor the administration side of things, but rather their focus is on the final product: How everything should look on our screens, since they are responsible for creating a concise and coherent unit out of all the elements in an anime. This is the biggest asset someone from a photography background would have in their transition to director.

Perhaps the most infamous case is the individual who finds himself almost universally hated around the industry and fans alike for toxic comments and behavior, Yutaka “Yamakan” Yamamoto. Starting with Kyoto Animation’s photography department back in the nineties, he would debut as second-in-command after Tatsuya Ishihara on The Melancholy Of Haruhi Suzumiya, this being prior to the Lucky Star fiasco where he deservedly found himself on his way out the door. In some ways his shortcomings as a director were related to the isolated background someone from photography would find themselves with, perhaps exacerbated by Kyoto Animation’s more insular methods, Yamamoto had no practical experience (aside from leading his own small department as director of photography). His shortcomings as a person are an entirely different story however, and are more likely to be the main reason he got what he deserved at the end of his run.

Another very famous case from this origin is Ei Aoki, director of Fate/Zero and the main force behind studio TROYCA. If you’ve ever wondered why his shows are known for their aggressive composite and some peculiar experiments with it now you do!

Girl’s Last Tour’s Takaharu Ozaki is certainly worth a mention as well, his strong use of lighting and cinematography techniques paint a pretty picture.

Recently, on the Boruto series, Takeru Ogiwara has been a major revelation, perhaps being one of the most talented directors in all of Naruto, a franchise which generally used to look pretty plain in this regard just a few years ago.

3DCGI

The newest of these origins has become a thing only very recently, so we have a limited catalog of these directors to speak about. They started to gain momentum as 3DCGI started to take a bigger part of productions in the industry throughout the last ten years.

The most famous ones are Tokyo Ghoul’s Shuuhei Morita and Vinland Saga’s Shuuhei Yabuta. Especially for the later, their talents are often employed on series which are adaptations of manga with very complex art which may find itself to be too much for regular hand-drawn animation to handle. Perhaps requiring a specific sense of tri-dimensionality and solidness to keep it together. Fortunately choreographing action scenes, whether it be in 2D or 3D, follow similar principles so those skill sets inevitably carry-over. Being able to construct the story board with the necessity (and limitations) of 3DCGI already in mind is also a huge advantage.

One of the main shortcomings of a 3D upbringing however, is the lack of connections in the 2D animation realm. It goes without saying but all non-full CGI projects will inevitably require animators with talent on paper and thus directors like Yabuta and Morita are at the mercy of whatever the studio can provide them, not always the worst case though, and friends can certainly be made after the fact, but something to keep in mind as well!

Miscellaneous

We’ve covered many of the major and also up-and-coming paths, but of course there are also those more niche. Sunao Katabuchi (In This Corner of the World) and Ryosuke Nakamura (Grimgar) started in the script writing field first, Nakamura especially can be considered one of the most complete directors in the industry, having knowledge of producing, animating, script writing, and even doing sound direction for his shows- the closest that one can come to doing an entire non-independent anime on their own.

Recently, renowned scriptwriter Mari Okada had her directorial debut on Maquia, supported by her pedigree as a successful anime scriptwriter, and working with known director Toshiya Shinohara to bring her vision to life. She even had a hand in the storyboards despite not having any real experience in the field! Although some may consider it just a marketing tactic by the movie’s producers to leverage her well-known name amongst anime fans, she undoubtedly showed real promise with it.

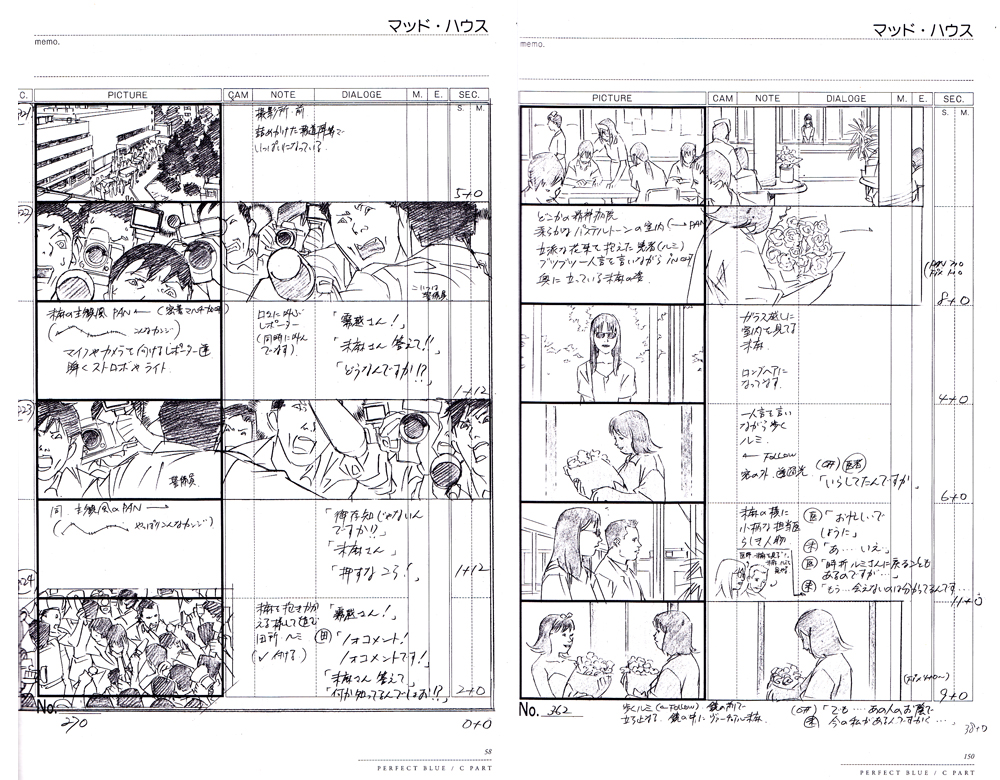

Satoshi Kon and Katsuhiro Otomo, even if they were pretty capable animators to begin with, were more acquainted with the manga industry than anime when they began their respective directorial careers. It’s certainly no secret upon looking at how intricate their storyboards were.

While both are legendary figures, it’s worth differentiating mainly that Otomo was already a star in the manga industry before he decided to jump on the animation train, while Kon’s background stems more from connections as an animator and a background artist.

With that ends our coverage of all the different, and in some cases, unique roads traveled by a host of talented individuals. Of course, a creative background is comprised of far more than just the previous job title one held, so while we can derive some meaning from it, do keep in mind it is not the whole picture, especially when it comes to some of the incredible minds we’ve discussed here. The biggest take-away can be found in the newer avenues, as production processes evolve and industry trends shift, there becomes a greater need as well as more opportunities for those that 20 years ago, had little chance. Who is to say what might come next either. Maybe one day we’ll see a voice actor directing, and yes, I’m aware Hideaki Anno is quite established in that regard!